Ute Chief Ouray of the Uncompahgre Ute tribe sought peace as a mediator during troubled times.

Chief Ouray was born November 13, 1833 (his year of birth is also given in 1820 by some accounts), amidst the shooting stars of the Leonid meteor shower, as if the universe knew that the child would grow to be a prominent figure in Colorado and national history. His name "Ouray" was chosen from the meteor shower, as it means "The Arrow" in Ute. And like his namesake, his path in life was clear: negotiate peace to protect his people, even in the face of opposition and controversy.

Early Days

While he rose to prominence as a chief in Colorado, Ouray was not born in our state, but around Taos, New Mexico, instead. His father, Guera Murah, was Jicarilla Apache and his mother was Ute. Interestingly, he was not raised by his parents. A Spanish family in the area brought him up, teaching him English and Spanish. It actually wasn't until later in his life that he learned his native tongues of Apache and Ute.

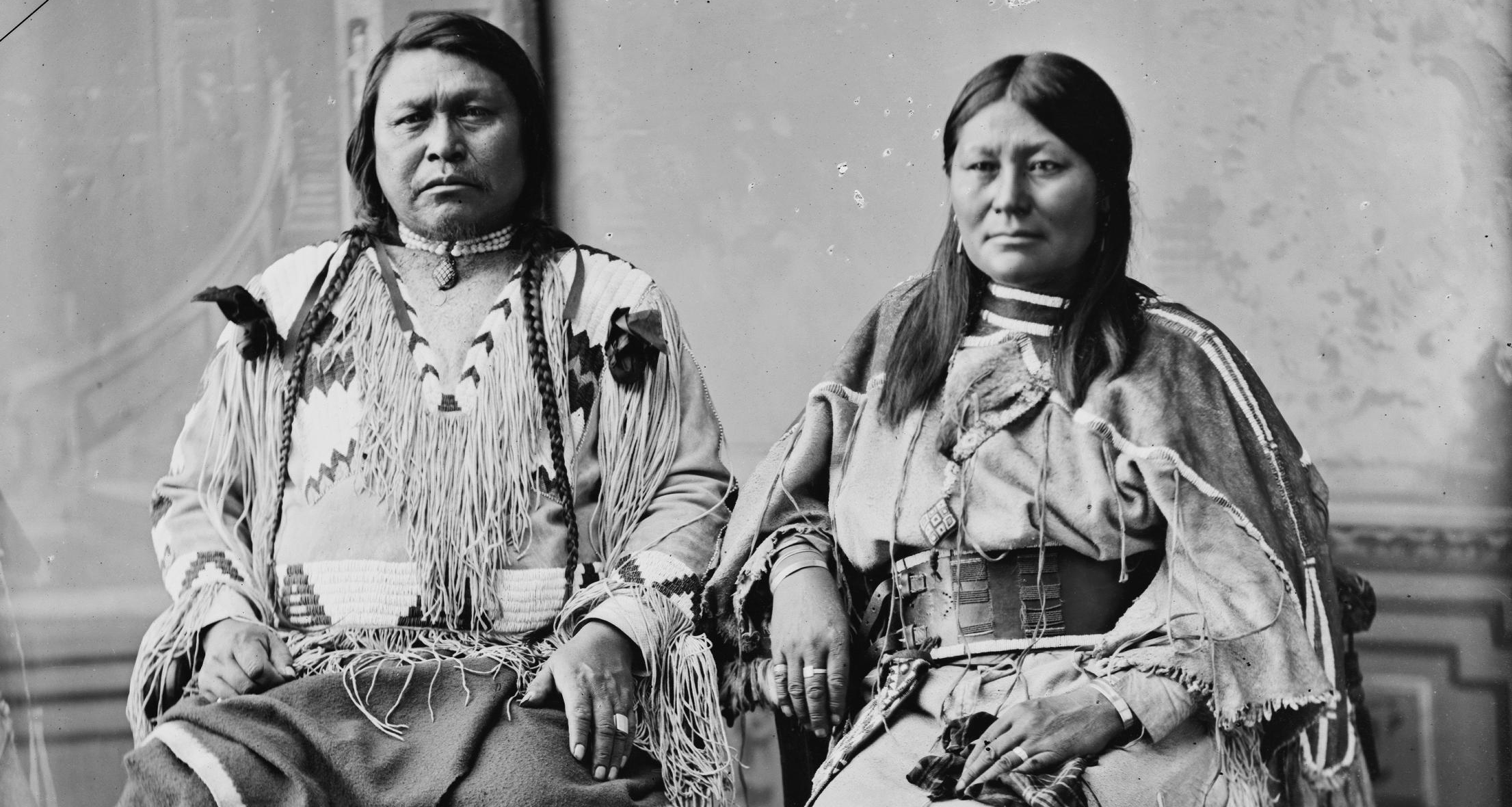

While not raised by them, Ouray was in touch with his parents, and he moved to Colorado at 17 to join them. Despite being Apache, his father was the chief of the Uncompahgre (Tabeguache) Ute tribe, where Ouray settled in and married his first wife, Black Water, who passed away during a Sioux attack, and had a son who went missing during that attack. He remarried Chipeta, a Kiowa Apache woman who had grown up with the Utes, in 1859. Even then, he was a strong hunter, fighter, and leader, setting him up for a larger role in the tribe's future.

Chief and Negotiator

Upon the death of his father in 1860, Ouray became chief of the tribe at the age of 27. Faced with an ever-growing population of white settlers encroaching on his land, Ouray felt the only option for his people's survival was co-existence. He firmly believed that, while treaties were not a welcome path, war with white people would likely mean the demise of native peoples. Choosing what he felt was the lesser of two evils, Chief Ouray became instrumental to the government as a treaty negotiator for his tribe, though he was not naive to what treaties meant.

“The agreement an Indian makes to a United States treaty is like the agreement a buffalo makes with his hunters when pierced with arrows. All he can do is lie down and give in," he is reported to have said.

All treaties he negotiated on behalf of his people were kept in good faith, and he protected the tribe's interests as fiercely as he could. Many of his negotiations were instrumental in keeping the Ute protected from the massacres and depredations that had befallen other Native American tribes at the time. Unfortunately, he also happened to be a leader in a time that saw a government hungry for land and the extinction of his way of life, as he knew it.

"He saw the shadow of doom on his people," said a 1928 Denver Post article, with a 2012 article summing up the hard path the chief walked as, "He sought peace among tribes and whites, and a fair shake for his people, though Ouray was dealt a sad task of liquidating a once-mighty force that ruled nearly 23 million acres of the Rocky Mountains."

Chief Ouray and Chipeta. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Not all Utes felt he was doing the right thing, and they vehemently opposed his actions. He came to be known as "The White Man's Friend," a term of endearment used by the government, but a slander used by other members of his tribe. There were attempts on his life, including one by his own brother-in-law, Saponvanero, who tried to kill him with an ax during a visit to Los Pinos Indian Agency in 1874.

Under the Treaty of Conejos in 1863 (Colorado Territory was established in 1861), Chief Ouray convinced the Utes to negotiate in order to protect hereditary lands, as he feared what would happen due to the influx of new people into the territory. That treaty, unfortunately, reduced their lands to 50 percent of what it had been. The tribe lost all lands east of the Continental Divide, including sacred land in Pike's Peak and Manitou Springs. The treaty guaranteed the tribe the western one-third of Colorado. In exchange for allowing roads and forts to be built on the land, the government promised sheep, cattle, and other provisions to encourage the tribe to get started with farming, but few of those promises were held, leaving many in dire straights.

The Treaty of 1868 came after the theft of settlers' livestock and an uprising gave the government a chance to obtain more Ute land. This was the treaty that would result in the creation of a reservation for the Ute. It was signed by 47 Ute chiefs, and Ouray hoped it would protect his people. He was hesitant to enter this treaty, but many of the tribe were struggling to survive, and he felt he needed to negotiate on their behalf.

When silver was found in 1872, the rush to mine it put the Ute land in greater jeopardy. Chief Ouray, with no little manipulation of the part of the government to "help" him find his son, and in turn keep him engaged in the treaty, exchanged mineral-rich property for provisions for his people. This Brunot Treaty of 1873 again saw the government balk at fulfilling their end of the deal.

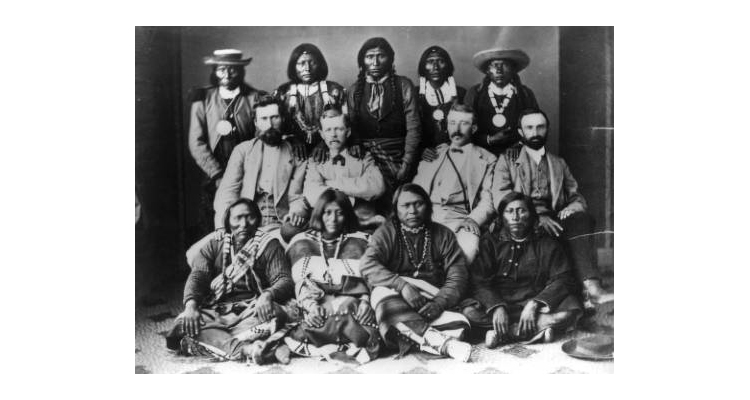

Courtesy of the Denver Library: Front row, left to right: Guero, Chipeta, Ouray, Piah, second row: Uriah M. Curtis, Major J. B. Thompson, Gen. Charles Adams, Otto Mears; back row: Washington, Susan, (Ouray's sister) Johnson, Jack, and John.

The Meeker Massacre signified the end of Ouray's negotiations on behalf of his people. Nathan Meeker plowed under race tracks and tried to force the nomadic tribes to settle down and farm, often with military force. Several chiefs sought peace with Meeker, but it ended in a fight, with hostages taken. Chief Ouray was able to get the warriors to release the hostages, whom he and Chipeta cared for in their home.

Unfortunately, despite his years of trying to reconcile white settlers and the Ute people, a final treaty was signed in 1880, which put them on reservations in Utah, and southern Colorado. Chief Ouray died that same year from Bright's Disease. His wife, Chipeta, accompanied her people to the new reservation on Utah and continued to fight for reinstatement of their ancestral land.

Leaving Behind a Legacy

Chief Ouray was secretly buried in Ignacio, Co., location of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, after his passing. In 1925, his bones were re-interred in a full ceremony at the Ignacio cemetery. The town of Ouray is also named after him.

Ouray made a mark on many people on his quest for peace. He traveled to Washington, D.C., several times to meet with presidents, and when President Rutherford B. Hayes met Ouray in Washington, D.C., he said that the Ute was "the most intellectual man I've ever conversed with."

After he passed away, the Denver Tribune wrote, "In the death of Ouray, one of the historical characters passes away. He has figured for many years as the greatest Indian of his time, and during his life has figured quite prominently. Ouray is in many respects…remarkable…pure instincts and keen perception. A friend to the white man and protector to the Indians alike.”

Share your thoughts with us in the comments.